Petrograd:

…standing suddenly alone and exposed in an open space, he watched a horseman gallop up, point a pistol in his face, and demand, ‘For or against the people?’

‘I am English,’ replied Ransome, helplessly.

‘Long live the English!’ shouted the horseman, and galloped away.

I’ve always thought that the Swallows and Amazons books of Arthur Ransome, with their multiple layers of imaginative reality and potent sense of independence, are particularly fine training material for readers. And I’ve assumed – as one does, about the things one likes – that his appeal was more or less universal, but his books do seem to have a peculiarly British appeal: they’re not available in Italy, for example, and even the more literary, nautically minded Americans I’ve mentioned him to haven’t heard of him.

I’ve always thought that the Swallows and Amazons books of Arthur Ransome, with their multiple layers of imaginative reality and potent sense of independence, are particularly fine training material for readers. And I’ve assumed – as one does, about the things one likes – that his appeal was more or less universal, but his books do seem to have a peculiarly British appeal: they’re not available in Italy, for example, and even the more literary, nautically minded Americans I’ve mentioned him to haven’t heard of him.

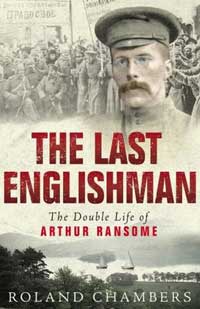

Perhaps this primarily British appeal explains the title of Roland Chambers’ new biography of Arthur Ransome, The Last Englishman. It’s a bit of an off-the-peg title, catchy but not particularly fitting, evoking an anachronistic quixotism that might have been more appropriate for Russell Miller’s Conan Doyle biography.

Sadly, the title’s symptomatic of a book that, while packed with interesting information, feels structurally ill-conceived.

Although The Last Englishman takes Ransome’s life from cradle to grave, the focus, and the bulk of the text, is based on the years Ransome spent in Russia, where he associated with Trotsky, Lenin, Karl Radek, and other key figures of the Revolution. Given this weighting towards the Russian years, it’s unfortunate that Ransome himself seems to slip out of focus here.

In Russia, after a brief section detailing his growing interest in Russian folk tales, Ransome becomes a distant figure, and much of the text is devoted to a potted history of the period, character giving way to chunks of history as Chambers reels off lists of skirmishes and political changes in what one reviewer has compared to GCSE-level writing. That was a little mean, and not entirely fair, but I see what he was getting at: these clusters of reeled-off facts don’t add to Ransome’s story. They’re not even presented from his perspective, which is fine in a history book, but not in a biography which, like a historical novel, should be careful to keep its protagonist at the centre of the story. As it is, what we have is a brief biography of Ransome’s early and later years, sandwiching a selective history of the Russian revolution, which occasionally drops in on Ransome, through a mention in an official telegram or an argument between a newspaper and a government department; the man himself feels almost entirely absent.

The problem may well be that Arthur Ransome was not really a key figure in the revolution, but it might have been more interesting – and better suited to the purposes of a biography – to keep the focus more tightly on him, and his experiences, even at the expense of the historical coverage. In this way, there may at least have been continuity between the fully realised Ransome who takes centre stage at the beginning and end of the book, and the name that’s mentioned in the middle.

Originally slated for a 2008 release, publication on The Last Englishman was delayed until this autumn, and I wonder whether this was at least partly an attempt to better resolve some of this conflict between biography and history. Whether or not that was the case, The Last Englishman as published is sadly one of those books that reminds us there’s a great story to be told, but doesn’t quite get to the heart of telling it.