Alex Clark on ‘The Stamp Works’

Wednesday, 9th July 2014.

In our latest ‘Stories behind Stories’ post, here’s Alex Clark on her experiences as an industrial archaeologist, and how they inspired her spooky tale ‘The Stamp Works’.

In our latest ‘Stories behind Stories’ post, here’s Alex Clark on her experiences as an industrial archaeologist, and how they inspired her spooky tale ‘The Stamp Works’.

Somewhere in Sheffield, some time around 2005, I walked across the charred floor of the Stamp Works.

It wasn’t called that, of course. I’ll pretend I won’t name it for legal reasons, although actually it’s because I’ve forgotten its name. It was a typical site, a derelict factory complex. I was there with three other archaeologists, sent to record the works before it was demolished.

The room in question was on the first storey. We had come to it on our way through the site which, like most factories of its age, had developed organically until it was a jumbled labyrinth of sheds, offices and workshops. In order to enter the next set of buildings we needed to climb a set of stairs, cross a room, and descend the other side.

The problem was the floor. It was a sagging timber funnel centred on a black hole. Joist stumps stuck out of the edges of the break where the fire had come through. At the weight of a footfall, the whole thing bounced like a boat in choppy water.

The two senior members of our team, experienced in this kind of situation, weighed it up and decided we’d walk round the edge of the room, sticking to the walls where the joists were most secure. The first time I did this was very, very scary. By the end of a week on site, however, I wouldn’t think twice about nipping back over the same floor to pick up another roll of film. In my story, it’s fear that leads the narrator into a dangerous situation. In real life, it’s familiarity that’s the real hazard.

I worked for five years as an historic buildings archaeologist. Almost all of the buildings I worked on were industrial, from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Forget Time Team: what most archaeologists in the country do is work commercially, which means they’re paid by developers to fulfil the legal obligation to record remains before they’re destroyed or altered.

When it comes to buildings, those remains are rarely anything very pretty. They’ve probably not been in use for ten or twenty years, often longer. The pigeons will have moved in. If you’re unlucky the squatters will have found a way in too. Like ghosts, they flit through the buildings, following complex routes (out through a first-floor window, across a lean-to roof, into a yard) which have nothing to do with the shuttered doors.

Once, in the middle of an entire block of abandoned houses in a blighted Lancashire town, I left my rucksack in the next room and returned to find my bank cards stolen. For four streets there was nothing but wasteland, and yet we were not alone. On the same site, I was busy drawing inside a vacant shop when my partner came running in, alarmed. ‘Did you see him?’ she said. I’d seen no-one. Whoever he was, he had walked behind me and out of the back of the building. We didn’t know where he came from. We didn’t know where he went. He was leading a parallel life to ours, seeing a different world, walking invisibly along secret paths. And what is that if not a haunting?

It was as a result of all of this that I conceived the idea of writing a ghost story set in an abandoned factory. As a keen fan of MR James, I loved stories of uncanny places with supernatural guardians. The old works I had seen seemed like the natural modern location for a slightly old-fashioned chilling ghost story: monumental, decaying, full of Gothic horror and adventure. It was a few years before I got round to actually getting it down on paper, but the result was ‘The Stamp Works’.

It was as a result of all of this that I conceived the idea of writing a ghost story set in an abandoned factory. As a keen fan of MR James, I loved stories of uncanny places with supernatural guardians. The old works I had seen seemed like the natural modern location for a slightly old-fashioned chilling ghost story: monumental, decaying, full of Gothic horror and adventure. It was a few years before I got round to actually getting it down on paper, but the result was ‘The Stamp Works’.

The description of the works itself came quickly: I’ve been to all of it. Not in the same place, or at the same time, but it’s all real. The stories that the narrator tells, too, are all real. They really did used to hang wallpaper with animal glue, and when the rain gets in, the resultant mushrooms really are a perfect yellow. In fact, the only thing in the Stamp Works that I’ve never encountered is the ghost.

When I came to write it, the story emerged rapidly, almost fully formed. I suspect that it had been sitting in my subconscious, incubating, for a few years. Though I didn’t direct its development – I certainly don’t recall plotting it – I can pinpoint the moment when I first thought of the idea of a ghost in a decaying factory.

The site was an old cutlery works. There were two of us sent to record it. It was a tortuous place, with only one entrance at the very end of a long, meandering series of boarded workshops. The doors were offset, so that within a few rooms of the entrance we totally lost sight of daylight. We picked our way through the dust, debris and bird corpses, lighting our way with a single torch, until my partner stopped abruptly and made an annoyed noise.

‘What’s up?’ I said.

‘I forgot the extension cable,’ he said. ‘If you stay here I’ll head back and get it now.’

He turned and wound his way back across the workshop, the bobbing light of the torch receding until, abruptly, it passed through a doorway and was extinguished.

I stood rooted to the spot, trying to stay calm. It was five minutes to the entrance, so ten at least until he came back. The darkness was complete. To the left of me, I heard a stealthy rustling, just on the edge of audibility.

‘It’s just birds,’ I said to myself, as I strained my eyes for the returning light. ‘Just birds.’

— Alex Clark

Read ‘The Stamp Works’ in our anthology There Was Once a Place, out now in paperback and ebook editions.

Richard Smyth and the First Person

Friday, 4th July 2014.

Here’s Richard Smyth with some thoughts on writing in the first person. Richard’s new novel, Wild Ink, is out now.

‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you.’– TS Eliot, ‘The Waste Land’

Yeah – who is the third? Who is that, bookending dialogue with he-saids and she-saids, commentating on proceedings with a curiously proper and well-spoken detachment, mind-reading without explanation, casually omniscient, incomprehensibly well-informed, inhumanly objective? Who are these Third People, and what are they doing in our novels?

I do most of my writing in the first person. My first novel, Wild Ink, is narrated by its main protagonist, the horridly decrepit but reliably wry Albert Chaliapin. My stories for The Fiction Desk, ‘Crying Just Like Anybody’ and ‘Chalklands’, adopted first-person perspectives, too. I’d seldom ever really stopped to wonder why – why have I so often preferred to step into my characters’ shoes, instead of maintaining a decent distance, an appropriate remove?

I do most of my writing in the first person. My first novel, Wild Ink, is narrated by its main protagonist, the horridly decrepit but reliably wry Albert Chaliapin. My stories for The Fiction Desk, ‘Crying Just Like Anybody’ and ‘Chalklands’, adopted first-person perspectives, too. I’d seldom ever really stopped to wonder why – why have I so often preferred to step into my characters’ shoes, instead of maintaining a decent distance, an appropriate remove?

The way in which language is used on a word-by-word sentence-level basis – style, to use a rather loaded word for it – is very important to me. Writing your stories from inside a character’s head gives you almost unlimited stylistic freedom. Turns of phrase and figures of speech can be used that, coming from the pen of an unidentified third-person narrator, would invite unhelpful questions about who on earth is telling this story, and why they talk the way they do. Complex, original language creates, just by existing, a speaker, a person, a character; do this with a nameless third-person narrator and you will be thought to be playing postmodern games with the reader.

It’s a little unfair, of course. There’s seldom any secret about who is telling the story: their name is right there on the title page. Any quirks of language, flights of invention or unexpected editorialising come, of course, from them.

But modern literature shies away from the self-identifying storyteller. And ‘shy’ is the word: it feels unseemly, importunate, to step into the story one is telling with a bold Dickensian ‘I’; for the modern author, it seems to invite the rebuke ‘Who on earth do you think you are?’ – meant either literally, in the assumption that the author is creating an ‘author’ character, that the narrator is not Richard Smyth but ‘Richard Smyth’, or figuratively and indignantly, to suggest that the author has overstepped the mark. Sure, some writers – Anthony Burgess, James Joyce – get away with it, pushing stylistic limits in third-person narration without ever explaining how or why. But, well, we aren’t all Burgess or Joyce.

Distinctions between first and third persons are not necessarily clear-cut. There are many instances of authors breaking the bonds imposed by third-person conventions by narrating through a secondary character – to each Jay Gatsby his Nick Carraway, to each Ahab his Ishmael. This gives the work an additional layer, another dimension; we are invited to view one character through the filter of another, a double refraction of reality. The catch here is that the narrator – while they may digress, switch between narratives, shift focus from character to character and indulge in other such authorial perks – may not be omniscient.

That may or may not be a problem. Only a true know-all can narrate War And Peace. In other novels, it’s necessary for the narrator to be in the dark (like John Self in Money, for instance).

Personally, I want to be where the fireworks are. I want to know first-hand what Gatsby’s going through. I want to read Ahab’s inner monologue! I want to get as close to the action as I possibly can, which often means taking one’s seat in between the character’s ears – even though what one sees in there might not be particularly pleasant. Good first-person narration brings you face to face with an honest and flawed humanity (if it’s honest, it’s inevitably flawed). For me, that’s really what fiction is for.

— Richard Smyth

Sarah Evans on ‘Mission to Mars: an A-Z Guide’

Wednesday, 2nd July 2014.

In the latest post of our ‘Stories behind Stories’ series, here’s Sarah Evans to tell us about the process of writing ‘Mission to Mars: an A-Z Guide’.

In the latest post of our ‘Stories behind Stories’ series, here’s Sarah Evans to tell us about the process of writing ‘Mission to Mars: an A-Z Guide’.With a long standing interest in physics (I was a theoretical physicist long before I started crafting stories) the idea of space travel has always been fascinating.

Last year, the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination prompted the airing of various TV documentaries about the first moon landing and, coincidently, I came across a web article looking at various projects – public and private – to send manned (possibly one-way) missions to Mars. Taken together, my imagination was immediately sparked.

The process of writing never takes a single path. Occasionally I move smoothly from initial idea to a coherent first draft. Other times writing is far more chaotic. A bit like solving a physics or maths problem: sometimes you ‘get it’ straight off; and other times you don’t. This time, I certainly didn’t. I started writing all sorts of scenes. Some on earth, others on Mars. Churning out wordcount was fine – loads to play with. But nothing settled. My document (labelled, unimaginatively, ‘Mars’) reached 9,000 words and counting. But I still didn’t know, not really, who my narrator was, I didn’t have a structure, and though I knew ‘what happened’ I was failing to inject any kind of suspense or surprise. The whole thing felt unremittingly dreary. How could a ‘Mission to Mars’ feel so boring?

Time for a major rethink.

Back in my days as a budding physicist, I couldn’t abide any of what I termed ‘waffle subjects’, by which I meant any school subject where answers to questions contained more words than equations. I loved reading in my spare time, but hated (really hated) writing myself, whether that was creative writing or essays. ‘Sarah doesn’t like long answers,’ my physics teacher once said. And that pretty much summed me up at the time.

Since (inexplicably) finding the urge to write fiction about eight years ago, I’ve learned the pleasures of churning out words and – as I would have termed it – waffle. But succinctness and precision play a big role in writing too. It’s hardly unusual for me to reduce initial wordcount by twenty, thirty, fifty percent. It’s less usual to reduce something ninefold.

But that’s what happened here.

The idea of a contrived structure – following the alphabet – isn’t entirely new and neither is it something that would generally appeal to me. I can’t really identify what it was that triggered the idea. Perhaps it had something to do with spotting our copy of Primo Levi’s ‘Periodic table’ on our shelves, or maybe the sight of my friend Rob Pateman’s book, ‘The second life of Amy Archer’, which has an A to Z section too. In any case, solutions to problems – be they mathematical or literary – are sometimes like that: the way in comes to you a bit out of the blue. Somehow the (highly unoriginal) phrase ‘A is for apple’ came to mind, alongside the idea that eating fresh produce was something astronauts might miss.

The idea of a contrived structure – following the alphabet – isn’t entirely new and neither is it something that would generally appeal to me. I can’t really identify what it was that triggered the idea. Perhaps it had something to do with spotting our copy of Primo Levi’s ‘Periodic table’ on our shelves, or maybe the sight of my friend Rob Pateman’s book, ‘The second life of Amy Archer’, which has an A to Z section too. In any case, solutions to problems – be they mathematical or literary – are sometimes like that: the way in comes to you a bit out of the blue. Somehow the (highly unoriginal) phrase ‘A is for apple’ came to mind, alongside the idea that eating fresh produce was something astronauts might miss.

And so it started.

Initially, I had no idea if I’d be able to get through the entire alphabet or not, though amidst those 9,000 words most letters got a look in from time to time. I still worried about how on earth (or Mars) I’d handle those awkward letters at the end.

But once I got off the ground, the whole thing become fun and ideas began to flow. Writing certainly wasn’t linear; I moved freely back and forth through the alphabet, it was still too long, but at last I had something I could play with and refine.

Once it was more or less there, I then had to ask myself, but is it any good? Usually I have some sort of an idea whether I’m pleased with something or not, and whether something is worth sending out on submission. This time was much harder to judge.

Bravado won out.

And I’m very glad it did. I’m delighted for my Mission to Mars to be launched by The Fiction Desk.

Read Mission to Mars: an A-Z Guide in our anthology There Was Once a Place, out now in paperback and ebook.

New books from Fiction Desk authors

Thursday, 5th June 2014.

This summer is going to be a busy one for our authors, with new novels and other bits and pieces coming out. Here’s a round-up of what to look out for:

Miha Mazzini: Crumbs (Out now)

Slovenian author Miha Mazzini‘s stories have appeared in two of our anthologies: Crying Just Like Anybody and New Ghost Stories. He’s written several novels, although only a few have been translated into English. The German Lottery (published by CB Editions) is well worth a read, and this year Freight Books have published a translation of his debut novel, Crumbs. Here’s the blurb:

The best-ever selling novel from the former Yugoslavia, this is a hilarious, anarchic, irreverent black comedy about national aspirations and wanting things you can’t have, re-published in the year that Scotland votes on independence.

Egon is an amoral but charismatic writer, living on the breadline in a grim, unnamed communist factory town in Slovenia prior to the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. With little evidence of his real literary ambitions, he makes ends meet by writing trashy romances under a pseudonym. When not searching out sex with as many women as possible, or slagging off the literary establishment, Egon is full of schemes to feed his pathological need for the ruinously expensive aftershave, Cartier pour L’Homme.

Around him Egon has gathered a motley crew of friends and acquaintances, each of whom also has an equally obsessive, unattainable ambition. Poet is desperate to have his verse published in a leather bound volume, Ibro is in love with Ajsha, a factory girl to whom he cannot utter a single word, while Selim is convinced he’ll marry Nastassja Kinski, the world-famous actress. As Egon’s attempts to secure more perfume become ever more degenerate, his grip on his own identity loosens. The consequences are messy, as grim as they are hilarious, and allude to a nation undergoing radical change.

Crumbs is not only a ribald, dirty realist satire – a modern European classic – but also a fascinating and utterly unique commentary on the pathology of self-determination. It’s publication in the months before Scotland votes on independence lends a surprising, alternative but authoritative perspective on the debate.

James Benmore: Dodger of the Dials (Out now)

This is the second book in James Benmore‘s series of novels revisiting the Artful Dodger from Oliver Twist. Written in the Artful’s voice, these novels show off James Benmore’s talents as an impersonator, and the stories feel as much performance as literature. (For the performance of another, very different character, see James Benmore’s story ‘Jaggers & Crown’ in All These Little Worlds. Here’s what publishers Heron have to say:

Two years on from the events of Dodger, Jack Dawkins is back as top-sawyer with his own gang of petty thieves from Seven Dials. But crime in London has become a serious business—and when Jack needs protection he soon finds himself out of his depth and facing the gallows for murder.

The evidence against him seems insurmountable, until a young reporter by the name of Oliver Twist takes up his cause. After freeing Jack from gaol, the pair must bury their past differences and join forces to hunt down the men who framed Jack and stole that which he treasures most.

Charles Lambert: With a Zero at Its Heart (Out now)

This short novel is constructed of 240 paragraphs, each of 120 words, forming a semi-autobiographical narrative. There are always tensions in Charles Lambert‘s writing between structure and emotion, and the personal and political, and I’m particularly excited to see how those tensions resolve themselves in this new book. With a Zero at Its Heart has already been well received by the Guardian. Charles will be launching the book in London next week. Here’s what publisher The Friday Project says:

24 themed chapters.

Each with 10 numbered paragraphs.

Each paragraph with precisely 120 words.

The sum of a life.

In his beautiful and haunting new book, Charles Lambert explores the fragmentary nature of memory, how the piecing together of short recollections can reveal a greater narrative. Through chapters tackling elemental themes such as Sex, Death, and Money, Lambert assembles the narrator’s moving life story. Executed with all the grace and finesse of his previous acclaimed work, this is an incredible artistic achievement, breathtaking in its simplicity yet awe-inspiring in its scope.

With cover and text design by the renowned designer Vaughan Oliver, With a Zero at its Heart is as beautiful to look at as it is to read.

William Thirsk-Gaskill: Escape Kit (Out now)

This is a short novella from William Thirsk-Gaskill, whose story ‘Can We Have You All Sitting Down, Please?’ appeared in Crying Just Like Anybody. It’s available as a limited edition paperback and Kindle ebook. Here’s the blurb from publishers Grist:

Bradley is a fourteen-year-old school boy who escapes his troubled home life to visit his grandparents in Stevenage. On the train there, he is held hostage by a deluded gunman who thinks he is an escaped PoW from WWII and that Bradley is a member of the Hitler Youth. Now Bradley must try and escape using his mobile phone. William Thirsk-Gaskill’s novella is a gripping and beautifully told tale of innocence and experience.

Richard Smyth: Wild Ink (June 2014)

Richard Smyth provided the title story for Crying Just Like Anybody, and a supernatural tale to New Ghost Stories. He’s published several books of non-fiction, but Wild Ink is his first novel. Here’s what the publisher (Dead Ink) says:

Wild Ink is a blackly comic story of friendship and envy, love and memory, booze and uproar, secrets and scandal. Albert Chaliapin is dead – or at least, he feels like he ought to be. He lives in a world occupied only by the ghosts of his former life (and his nurse, who can’t even get his name right). Then, one day, his past – in the form of a drunk cartoonist, a suicidal hack and a corrupt City banker – pays a visit, and Chaliapin is resurrected, whether he likes it or not. He doesn’t, much.

Someone’s sending him some very strange cartoons. Someone’s setting off bombs all over London. Someone’s been up to no good with some very important people. This is no job for a man wearing pyjamas. Will Chaliapin make it out alive? And is being alive, when it comes down to it, really all it’s cracked up to be?

Jo Gatford: White Lies (July 2014)

Jo Gatford, who won our 2014 flash fiction competition, is also celebrating the publication of her debut novel from Legend Press. White Lies takes a look at the way a family’s secrets are exposed when the father develops dementia. Here’s the blurb:

When Matt’s half-brother Alex dies, his father refuses to hold onto the memory of his favourite son’s death. It was hard enough the first time, but breaking his dad’s heart on a weekly basis is more than Matt can bear.

Peter, Matt’s father, is terrified his dementia will let slip the secrets he’s kept for thirty-five years. Unable to distinguish between memory and delusion, he pursues one question through the maze of his mind: Where’s Alex?

Faced with the imminent loss of his father, Matt is running out of time to discover the truth about his family. Tortured by his failing memory, Peter realises that it’s not just the dementia threatening to open his box of secrets, but his conscience, too.

Winners of the 2014 Flash Fiction Competition

Thursday, 6th March 2014.

It’s time to announce the winners of our 2014 Flash Fiction Competition. We had a lot of great entries this year, and putting together the shortlist has been tricky. So tricky, in fact, that we’ve increased the number of finalists from the planned four to six.

This year’s finalists, in no particular order, are:

- Nik Perring, with ‘Loss Angina’

- James Collett, with ‘Little Bird Story’

- Sarah Evans, with ‘Mission to Mars — an A to Z Guide’

- Dan Purdue, with ‘The Guy in the Bear Suit’

- Die Booth, with ‘Badass’

- Cindy George, with ‘Colouring In’

And the overall winner is:

- Jo Gatford, with ‘Bing Bong’

Thanks again to everybody who took part in our competition this year, and congratulations to the winners!

I’ll be in touch with the winners in the next few days, and all of the above stories will appear in an upcoming Fiction Desk anthology, so keep an eye out for that.

Our 2014 Ghost Story Competition is now open!

Thursday, 27th February 2014.

Today we’re launching the 2014 edition of our annual ghost story competition.

Today we’re launching the 2014 edition of our annual ghost story competition.

The first prize this year is £500, with at least five finalists each receiving £100. (This may go up to ten, depending on the entries we receive.)

For more information, see the ghost story competition page in our submissions area. And if you need inspiration (or just fancy a good read), pick up or download a copy of our anthology New Ghost Stories, which includes last year’s winners.

Announcing the Fiction Desk Writer’s Award for New Ghost Stories

Wednesday, 26th February 2014.

The winner of the Fiction Desk Writer’s Award for our latest anthology, New Ghost Stories, is… Jason Atkinson, for his story ‘Half Mom’. Congratulations Jason!

The winner of the Fiction Desk Writer’s Award for our latest anthology, New Ghost Stories, is… Jason Atkinson, for his story ‘Half Mom’. Congratulations Jason!

The Writer’s Award is voted for by the contributors to the anthology, and along with the acclaim of his peers, Jason receives £100.

‘Half Mom’ is the third story we’ve published by Jason, who made his Fiction Desk debut in our very first anthology, Various Authors, with the story ‘Assassination Scene’. His story ‘Get on Green’ later appeared in All These Little Worlds.

We’ll look forward to featuring more of Jason’s stories in future; in the meantime, why not pick up (or download) a copy of New Ghost Stories and read his winning story for yourself.

Eloise Shepherd on ‘Journeyman’

Thursday, 13th February 2014.

Here’s Eloise Shepherd to talk about her story ‘Journeyman’, which features in our anthology New Ghost Stories.

Here’s Eloise Shepherd to talk about her story ‘Journeyman’, which features in our anthology New Ghost Stories.

I wanted to write a ghost story about failure. Not high stakes failure, but a long defeat. Boxers carry failure so openly, when a boxer loses it’s written through cuts, gashes and broken bones. To lose a fight is to be taken apart, on a well-lit stage with a crowd baying for your blood. So many boxers in this country (the so called ‘Journeymen’ of the title) go in to lose, and this story started with my fascination with that long, conscious failure.

I have boxed competitively for a few years now. It isn’t my natural world but it has been startling. A quick introduction to the level of violence inside yourself.

The story itself, the initial moment with the bath, came from a boxer I used to train with. He was the king of journeymen, almost every week he went into the ring and lost. He is probably also one of the best boxers I’ve ever worked with (and I have worked with boxers without a defeat on their records and with nice shiny belts on their walls).

He was generous enough to let me use that image and I made a different person around that idea of going in and getting beaten up for a living. And the more profound and relatable failure was a man unable to connect to his sons, losing them and himself with fear closing in. But, that whole time, trying really hard. I’m more scared of that than any dead thing.

He was generous enough to let me use that image and I made a different person around that idea of going in and getting beaten up for a living. And the more profound and relatable failure was a man unable to connect to his sons, losing them and himself with fear closing in. But, that whole time, trying really hard. I’m more scared of that than any dead thing.

For this story, all that work boxing for all these years was great research. A little transformation, taking ‘being hit’ into ‘being creative’. Before you go in to box you wrap your hands. You take a few metres of soft, slightly stretchy cloth and encase your knuckles before you even get to putting on gloves. You do this because, physiologically, hands are meant not for hitting, but to hold.

I can’t imagine this will be the last story about boxing I write. It’s a process that takes me to what scares me, in and outside myself.

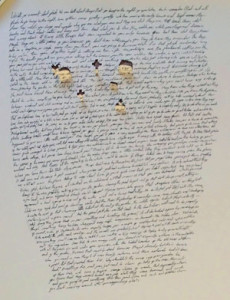

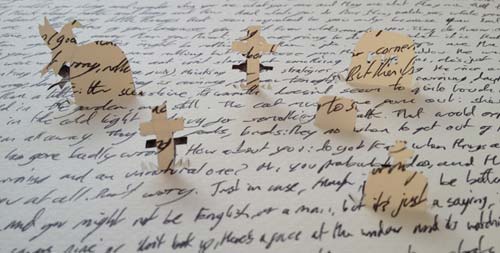

Designing the cover for New Ghost Stories

Thursday, 16th January 2014.

The cover for New Ghost Stories, our sixth anthology, is pretty straightforward, but also a little bit revolutionary — at least by our standards. The covers for the first five volumes were simple photographs, with very little processing. They followed fixed rules: everything had to be in front of the camera, and only paper and the written — or printed — word could be featured in the photograph. New Ghost Stories was originally intended to follow those rules, but ended up breaking them in a last-minute rush to get the files to the printers.

The original plan was to repeat the cover design from our first anthology, Various Authors, but with gravestones in place of the figures from the original cover.

The original plan was to repeat the cover design from our first anthology, Various Authors, but with gravestones in place of the figures from the original cover.

Where the text on the cover of Various Authors is a rambling mission statement for the series, the text on New Ghost Stories is an equally rambling, stream-of-consciousness ghost story, made up on the spur of the moment to fill the page. (Don’t worry: the cover is the only place in a Fiction Desk anthology where you’re likely to find much in the way of stream-of-consicousness prose.)

However, when the gravestones were cut out, they didn’t really work as well as the original figures had: there’s something, well, lifeless about gravestones, even with the addition of the bird from Richard Smyth’s story (er, top left).

With a couple of hours to go before the files were due at the printers, there wasn’t time to start a new design from scratch. I ended up flattening the gravestones back down into the paper, and taking various shots of the text. I layered these on the computer with varying levels of opacity, altering the colours and inverting the top layer. There was a brief flirtation with the use of a ribbon to hold the title — see the photo at the top of this post — and the cover went off to the printers with minutes to spare.

With a couple of hours to go before the files were due at the printers, there wasn’t time to start a new design from scratch. I ended up flattening the gravestones back down into the paper, and taking various shots of the text. I layered these on the computer with varying levels of opacity, altering the colours and inverting the top layer. There was a brief flirtation with the use of a ribbon to hold the title — see the photo at the top of this post — and the cover went off to the printers with minutes to spare.

It could have wound up as a complete dog’s breakfast, but actually I’m rather pleased with the cover of New Ghost Stories. And breaking the rules once has set a precedent for the future. Anything could happen… now, where’s my scalpel?

Julia Patt on ‘At Glenn Dale’

Monday, 13th January 2014.

Julia Patt’s story ‘At Glenn Dale’ opens our latest anthology, New Ghost Stories. Here, she talks about legend tripping and the real hospital that inspired the story.

Abandoned buildings have a kind of gravity.

Abandoned buildings have a kind of gravity.

I don’t mean seriousness—I mean a gravitational pull, not unlike that of a planet. A drawing in. Not everyone notices, but it’s there, something beckoning, saying: ‘Just one look… don’t you want to see?’

The really powerful places are the ones with a lot of history, maybe even a whole mythology around them, some of it true, most of it not. And those sites attract legend trippers: teenagers and young adults daring each other to take one step further inside, just a little closer to the shadows. Those are the places where kids go to prove themselves.

Like Glenn Dale.

Yes, it’s a real place, it really did serve as a TB hospital during the twentieth century, and it has stood empty for over thirty years. For a while, it seemed like the state was going to knock it down, but so far it has lingered, slowly collapsing of its own accord. I grew up about ten minutes from the hospital grounds, just outside of Washington, DC. As a teenager, I probably frequented Glenn Dale half a dozen times—a total dilettante by my protagonist Danny Fitzer’s standards. But even if you only venture there once, the hospital sticks in your imagination. Not only for what it is now and was then, but for the stories people tell about it, especially the ones that aren’t, strictly speaking, historically accurate. (I’m personally fond of the mental institution yarns.)

Yes, it’s a real place, it really did serve as a TB hospital during the twentieth century, and it has stood empty for over thirty years. For a while, it seemed like the state was going to knock it down, but so far it has lingered, slowly collapsing of its own accord. I grew up about ten minutes from the hospital grounds, just outside of Washington, DC. As a teenager, I probably frequented Glenn Dale half a dozen times—a total dilettante by my protagonist Danny Fitzer’s standards. But even if you only venture there once, the hospital sticks in your imagination. Not only for what it is now and was then, but for the stories people tell about it, especially the ones that aren’t, strictly speaking, historically accurate. (I’m personally fond of the mental institution yarns.)

Starting this story—eight years ago now—I knew I wanted to write about Glenn Dale, but I never wanted to write about my own experiences with it. Nor did I really want to recount its history; that kind of nonfiction never seems to do the hospital justice. So I went for fiction.

Unsurprisingly, my first attempt fell far short. I’d tried to wedge a story into the setting. By the end of it, Glenn Dale took over the whole affair and completely overshadowed my characters and their concerns. I tossed the draft and wrote other stories for a while.

Then, during a visit home, I returned to the hospital, wandered around the buildings, and narrowly avoided getting scolded by the policeman who patrols the grounds on a daily basis (sorry, sixteen-year-old self). It occurred to me in the middle of walking the corridors and reading the various graffiti that I needed a protagonist who loved Glenn Dale. Who would go back to the hospital again and again, searching out its mysteries. Who did want to see, who would linger in the dark longer than everyone else.

In other words, I needed Danny Fitzer, who is not one particular boy from high school, but several, many of them legend trippers, all of them wanting to be the bravest and the coolest, which Glenn Dale gave them, in its way. But of course, I thought, that requires danger, real danger.

In other words, I needed Danny Fitzer, who is not one particular boy from high school, but several, many of them legend trippers, all of them wanting to be the bravest and the coolest, which Glenn Dale gave them, in its way. But of course, I thought, that requires danger, real danger.

The earliest version of ‘At Glenn Dale’ began to evolve after that. There was still the matter of my pseudo-antagonist, Mark Dooley, and the hospital itself, which became like a third character in the story, and I spent much of my writing time trying to get the details of the place just right. This became another source of difficulty, as a mentor of mine pointed out: ‘You know, X would be a much stronger detail if it were really Y.’

‘But that’s not how it is,’ I would stubbornly insist.

Which is the trouble for all writers when we set out to depict real places, real people, and real events. There is the tension between telling it like it is and telling a good story. Real places are often inconvenient and annoyingly inflexible when it comes to layout and history. And although I had notes and pictures, even my memories and impressions of the hospital were inaccurate. I emailed and called a few of my friends to ask if they remembered such and such room or hallway or building.

Which is the trouble for all writers when we set out to depict real places, real people, and real events. There is the tension between telling it like it is and telling a good story. Real places are often inconvenient and annoyingly inflexible when it comes to layout and history. And although I had notes and pictures, even my memories and impressions of the hospital were inaccurate. I emailed and called a few of my friends to ask if they remembered such and such room or hallway or building.

They gave me different, sometimes contradictory answers. And the more we talked, the more I understood that my Glenn Dale was not everyone’s Glenn Dale. That all of us remembered the hospital a little differently, remembered even our shared stories differently. And the real often blurred with the legend, what we had heard blending with what we knew.

I stopped fussing over minutiae after that and made changes where it seemed beneficial. Consequently, the Glenn Dale in ‘At Glenn Dale’ belongs not to me or my friends or the historical record, but to Danny Fitzer and the story’s narrators.

And, of course, the ghosts.

New Ghost Stories is available now in paperback, Kindle, and iTunes formats. You can see more photographs of the real Glenn Dale here.